Mountain Sickness Risk Assessment Tool

Your Trek Details

Symptom Checker

Select any symptoms you've noticed:

When you trek above 2,500 meters, mountain sickness refers to a range of symptoms that appear as the body struggles with lower oxygen levels. It can turn an exciting summit into a miserable struggle, but a few smart habits can keep you breathing easy and enjoying the view.

Quick Takeaways

- Start low, climb high - give your body time to adapt.

- Stay hydrated, but avoid over‑drinking.

- Eat balanced carbs and moderate protein before and during ascent.

- Consider preventive meds like acetazolamide if you know you react strongly.

- Know the warning signs of HAPE and HACE and act fast.

What Exactly Is Mountain Sickness?

Mountain sickness, also called altitude sickness, groups three main conditions:

- Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) - headache, nausea, fatigue.

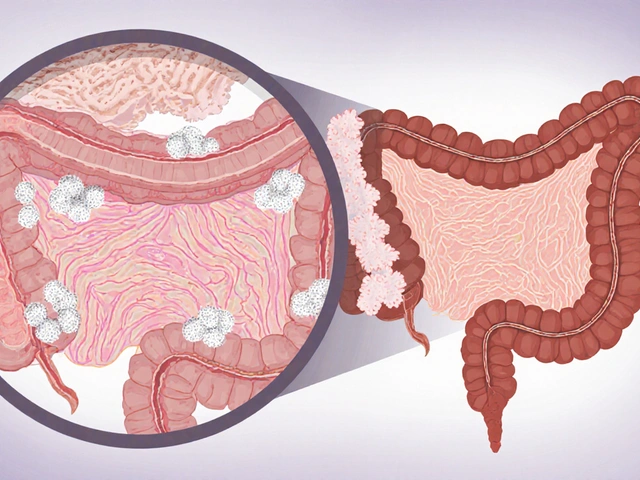

- High‑Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) - fluid buildup in the lungs, severe shortness of breath.

- High‑Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) - brain swelling, confusion, loss of coordination.

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema is a life‑threatening condition where fluid leaks into the lungs, reducing oxygen exchange and High Altitude Cerebral Edema involves swelling of brain tissue, leading to altered mental status. Recognizing which stage you’re in guides the right response.

How Acclimatization Works

Acclimatization is the body’s natural process of adjusting to lower oxygen by producing more red blood cells and increasing breathing rate takes time-usually 1‑2 days for every 300‑500 meters gained. Rushing the climb overwhelms this process and triggers symptoms.

Practical steps:

- Spend a night at an intermediate camp before pushing higher.

- Follow the "climb‑high, sleep‑low" rule: ascend during the day, descend to a lower altitude for sleep.

- Keep daily elevation gain under 500 meters after the first 3,000 meters.

Hydration and Nutrition Basics

Dehydration mimics many altitude‑related symptoms, so staying hydrated is non‑negotiable. Aim for 2‑3L of fluid per day, adjusting for sweat and temperature. Water shouldn’t be the only source; electrolytes help retain fluid and prevent cramping.

Food matters too. Carbohydrates provide quick energy and reduce breathing effort. A typical snack plan could be:

- Breakfast: oatmeal with dried fruit and nuts.

- Mid‑morning: trail mix (30% nuts, 70% dried fruit).

- Lunch: whole‑grain wrap with lean turkey, cheese, and hummus.

- Afternoon: energy gel or honey‑sweetened granola bar.

Limit heavy, fatty meals at high altitude-they slow digestion and increase nausea.

Preventive Medications: When and How to Use Them

Most trekkers manage fine with proper pacing, but for those with a history of AMS or who must ascend quickly, medication can be a safety net. Two commonly used drugs are:

| Drug | Typical Dose | When to Start | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetazolamide | 125mg twice daily | 24hours before ascent | Tingling, increased urination, mild metallic taste |

| Dexamethasone | 2mg every 12hours | At the first sign of severe AMS or prophylactically for very rapid climbs | Insomnia, mood changes, elevated blood sugar |

Consult a healthcare professional before starting any drug, especially if you have kidney issues or are pregnant. Carry a small emergency supply, but never rely solely on medication-proper ascent strategy remains essential.

Recognizing Early Warning Signs

Early AMS can be subtle. Use this quick checklist each morning:

- Headache that worsens with motion?

- Feeling unusually tired or short of breath at rest?

- Nausea, loss of appetite, or dizziness?

If you tick any box, halt further ascent, hydrate, and consider a descent of at least 300 meters. For HAPE or HACE signs-persistent cough with frothy sputum, rapid breathing, confusion, or inability to walk-descend immediately and seek emergency care.

Gear and Planning Tips

Some equipment can make a difference:

- Pulse Oximeter - checks blood‑oxygen saturation; values below 90% warrant caution.

- Insulated, breathable jacket - protects against cold‑induced vasoconstriction.

- Lightweight sleeping bag rated for sub‑zero nights - keeps core temperature stable.

- Map or GPS with altitude layers - helps plan gradual elevation gains.

Before you set out, map your route with elevation profiles. Identify natural rest spots every 600‑800 meters and mark emergency evacuation points.

What to Do If Symptoms Appear

- Stop climbing and sit or lie down.

- Drink 500ml of water with electrolytes.

- Take a dose of acetazolamide if you’ve pre‑planned it.

- If symptoms worsen after 12‑24 hours, descend at least 300‑500 meters.

- For HAPE/HACE, administer supplemental oxygen if available and arrange evacuation.

Remember, descent is the most effective treatment. Rushing back up rarely helps and can be dangerous.

Checklist Before Your Next Hike

- Know the maximum altitude and plan acclimatization stops.

- Pack a pulse oximeter and a basic first‑aid kit.

- Test preventive meds with your doctor ahead of time.

- Hydrate steadily for 48hours before the trek.

- Review the early‑warning symptom list each morning.

- Set a “no‑go” altitude limit based on how you feel.

By respecting your body’s limits and using these practical steps, you’ll dramatically cut the risk of mountain sickness and keep the focus on breathtaking vistas rather than medical emergencies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I prevent mountain sickness without medication?

Yes. Gradual ascent, proper hydration, balanced carbs, and nightly rest at lower elevations are the most reliable natural safeguards. Most trekkers avoid severe AMS by following the "climb‑high, sleep‑low" rule.

How much water should I drink at 3,500m?

Aim for 2.5-3L per day, split into regular sips. Add electrolyte tablets or sport drinks to replace salts lost through increased breathing.

What is the best time to start acclimatization?

Begin at least two days before reaching 2,500m. Spend a night at a base camp, then move no more than 300‑500m per day above that level.

Are there any foods that help with altitude?

Complex carbs like oatmeal, rice, and whole‑grain breads supply quick energy. Small amounts of caffeine can stimulate breathing, but avoid excess as it dehydrates you.

When should I use a pulse oximeter?

Check your SpO₂ each morning and after any period of exertion. Values below 90% indicate you should stop ascending and consider descending.

Wow, nothing like a bit of hypoxic ventilatory response to spice up your weekend trek, right? Just remember to pace yourself, keep that alveolar PO2 up, and don’t forget the portable oximeter-because who doesn’t love a little data‑driven panic at 3,500 m? Stay chill, stay hydrated, and enjoy the stunning view of your own mortality.

Great rundown! 👍 The “climb‑high, sleep‑low” rule really does the trick, and sipping electrolyte‑rich fluids keeps you from feeling like a wilted plant. If you ever feel the early headache, just pause, take a breather, and remember you’ve got this-one step at a time.

Imagine the mountain as a stern philosopher, whispering riddles of thin air into your lungs, demanding humility before its peaks. Each breath becomes a stanza, each step a line in an epic poem where the protagonist must choose surrender or ascent. The true test lies not in the summit’s height but in the mind’s willingness to dissolve its ego into the clouds.

Acclimatization, as the body’s ingenious adaptation mechanism, unfolds over a cascade of physiological adjustments that many trekkers overlook in their zeal to reach the summit. First, the increase in erythropoietin stimulates red blood cell production, thereby enhancing the blood’s oxygen‑carrying capacity, a process that can take several days to manifest fully. Simultaneously, the respiratory centre in the medulla ramps up ventilation, a response known as the hypoxic ventilatory drive, which provides immediate but often uncomfortable relief from hypoxia. This heightened breathing rate, however, can lead to respiratory alkalosis, prompting the kidneys to excrete bicarbonate in order to restore acid‑base balance. The resultant shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve permits more efficient oxygen unloading at the tissue level, a subtle yet vital benefit for endurance in thin air. While all of these mechanisms are marvelously orchestrated, they demand time-generally a gain of 300‑500 m per day after reaching the 2,500 m threshold is the gold standard. If you ignore this pacing and sprint upward, the cascade is interrupted, and you risk a cascade of symptoms ranging from mild headache to full‑blown HACE. Hydration, often trivialized, plays a pivotal role because plasma volume must expand to support the increased cardiac output required at altitude. Yet, many trekkers over‑drink, leading to hyponatremia, which paradoxically mimics altitude sickness and can be just as dangerous. Nutrition, too, must be calibrated; complex carbohydrates provide the rapid glucose needed for the heightened metabolic demand, whereas heavy fats can slow gastric emptying and exacerbate nausea. In practice, a balanced snack of oats, dried fruit, and a modest amount of nuts keeps blood sugar stable without overloading the digestive system. It is also prudent to carry a pulse oximeter, not as a gimmick, but as a quantitative checkpoint-values consistently below 90 % warrant a pause or descent. The mental aspect should not be dismissed; the anxiety of suffocation can amplify perceived breathlessness, creating a feedback loop that accelerates deterioration. Therefore, mindfulness techniques, such as controlled breathing exercises, can serve as a simple yet effective buffer against panic. In summary, respect the body’s tempo, hydrate intelligently, fuel wisely, and monitor your SpO₂; these fundamentals collectively safeguard you from the mountain’s hidden perils.

Oh sure, just ignore every piece of science and power‑walk up 1,000 m per hour because “adventure” apparently means “ignore your own biology”.

Respect yourself and the mountain dont gamble with life its not a video game 😒

We are but dust on a cliffside the mountain watches and judges our folly

You've got this! Keep the pace steady, sip that water, and remember every summit starts with a single, confident step.

Exactly, maintaining a moderate ascent rate and using the “climb‑high, sleep‑low” schedule maximizes acclimatization while minimizing AMS risk. Additionally, consider a brief rest day at 2,800 m to let the hematocrit stabilize before pushing higher.

From the rooftops of the Andes to the lofty peaks of the Himalaya, every culture weaves its own tale of sky‑bound reverence, reminding us that altitude is as much a shared story as a physical challenge.

its ez peasy if u just drink lotsa water.

The guide’s checklist you posted hits all the critical points-hydration, pacing, and symptom monitoring-making it a solid reference for anyone planning a high‑altitude trek.

Indeed, and beyond the logistics, the emotional resilience you build on the trail often translates into a deeper appreciation for the world below, turning each summit into a personal epiphany.

Dear fellow adventurers, I wholeheartedly endorse the comprehensive approach outlined above; by integrating disciplined acclimatization protocols with thorough pre‑expedition medical consultation, we significantly mitigate the hazards of mountain illness while preserving the joy of exploration.

Absolutely agree-let's also add a quick reminder to pack a portable charger for the pulse oximeter, because staying powered up is just as essential as staying hydrated.

When the wind howls across the ridge and the air thins to a whisper, the mountain tests not only your muscles but the very core of your resolve. Each heartbeat becomes a drum echoing through the stone, urging you to confront the inevitable fatigue. Yet within that struggle lies a quiet triumph, a moment where breath and spirit align in harmonious defiance of the altitude’s cruel grip. Embrace that pulse, for it is the true reward of any ascent.