Why do some people struggle to lose weight even when they eat less and exercise more? The answer isn’t just willpower. It’s biology. Obesity isn’t simply a result of eating too much or moving too little. It’s a complex disease rooted in how your brain and body regulate hunger, energy use, and fat storage. Understanding this helps explain why diets often fail-and why new treatments are finally making a difference.

The Brain’s Hunger Switches

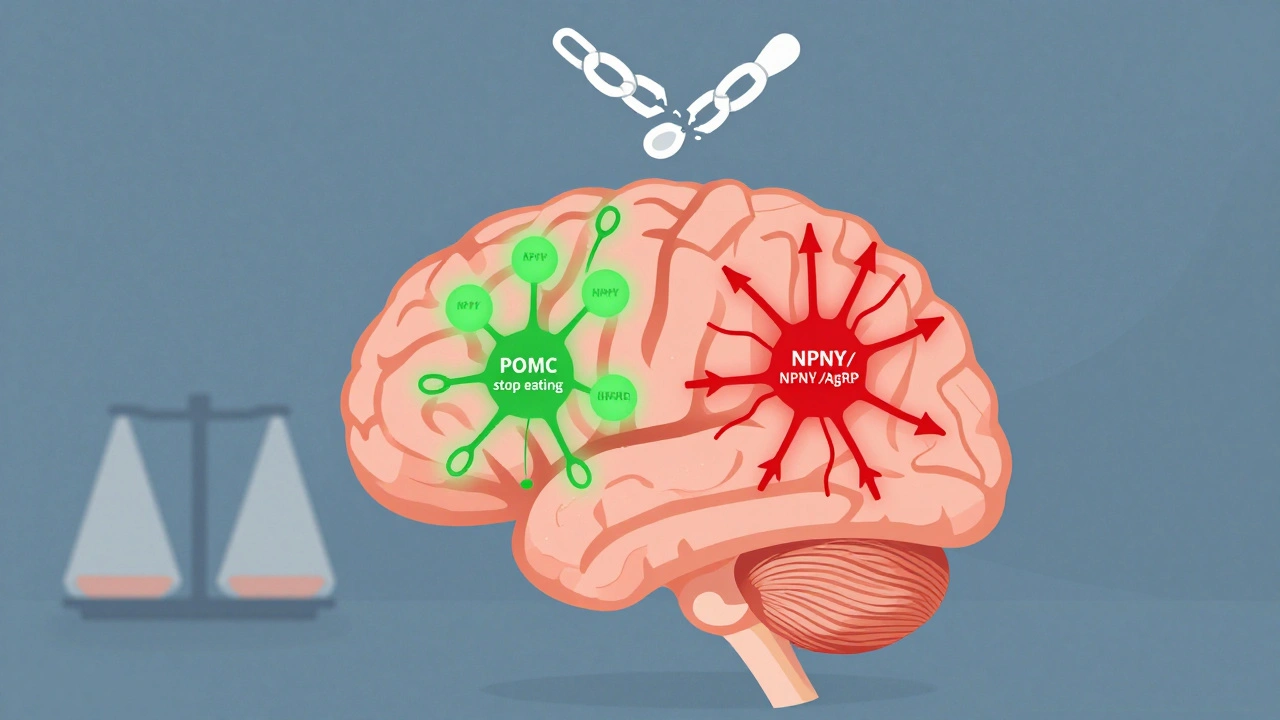

Your hypothalamus, a tiny region deep in your brain, acts like a control center for appetite. It’s packed with two opposing teams of neurons that constantly balance hunger and fullness. One team, made up of POMC neurons, releases chemicals that tell you to stop eating. The other, NPY and AgRP neurons, scream for more food. Normally, these systems keep your weight stable over time. But in obesity, this system gets rewired. Leptin, a hormone made by fat cells, should tell your brain you have enough stored energy. In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, they spike to 30-60 ng/mL-yet the brain stops listening. This is called leptin resistance. It’s the main reason most people with obesity aren’t hungry because they’re starving-they’re hungry because their brain thinks they’re starving. Ghrelin, the only known hunger hormone, behaves differently too. It rises before meals in everyone, but in people with obesity, it doesn’t drop as much after eating. That means you feel hungry sooner and longer. Studies show that activating AgRP neurons in mice can make them eat 300-500% more food in minutes. In humans, this same circuit runs on autopilot when leptin signaling fails.How Insulin and Other Hormones Get Caught in the Loop

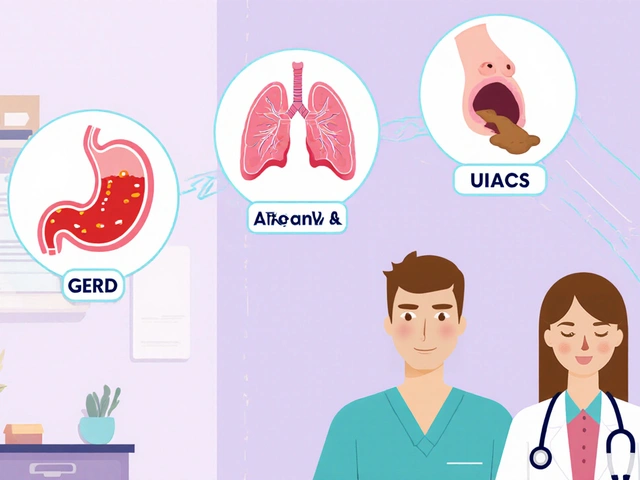

Insulin isn’t just for blood sugar. It also crosses into the brain and tells your hypothalamus to reduce appetite. In healthy people, fasting insulin levels are 5-15 μU/mL. After a meal, they rise to 50-100 μU/mL-and that’s supposed to help you feel full. But in obesity, insulin resistance spreads to the brain. Even when insulin levels are high, the appetite-suppressing signal gets blocked. Then there’s pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after meals to slow digestion and reduce hunger. In most people, PP levels hover between 50-100 pg/mL. But in 60% of those with diet-induced obesity, levels drop to 15-25 pg/mL. That means your body doesn’t send the “I’m done eating” signal properly. The same thing happens in Prader-Willi syndrome, a rare genetic disorder with extreme overeating. Estrogen plays a hidden role too. After menopause, women often gain belly fat-even if their diet doesn’t change. That’s because estrogen helps regulate energy balance. When estrogen drops, so does the brain’s ability to suppress appetite and boost calorie burning. Mouse studies show that removing estrogen receptors leads to 25% more eating and 30% less energy use.

The Cellular Breakdown: When Signals Go Silent

Inside brain cells, a chain reaction of molecular signals normally carries the message from leptin and insulin to shut down hunger. One key pathway is PI3K/AKT/FoxO1. When leptin binds to its receptor, it turns on PI3K, which activates AKT, which then blocks FoxO1-a protein that drives hunger. In obesity, this chain breaks. Inflammation from excess fat activates JNK, a stress enzyme that blocks PI3K signaling. The result? Leptin can’t get through. Another player is mTOR, a cellular sensor that responds to nutrients. When activated, mTOR tells the brain you’ve had enough. Stimulating mTOR in the hypothalamus reduces food intake by 25% in mice. But in obesity, mTOR signaling becomes sluggish, especially with high-fat diets. This isn’t just about calories-it’s about how your cells interpret those calories. Even serotonin, a neurotransmitter linked to mood, affects appetite. Some studies say it works through 5HT2C receptors on POMC neurons. Others argue it’s mostly through 5HT1B receptors that shut down NPY neurons. The debate continues, but one thing’s clear: messing with serotonin pathways can reduce food intake. That’s why some weight-loss drugs target these receptors.Why Diets Often Fail (And What Actually Works)

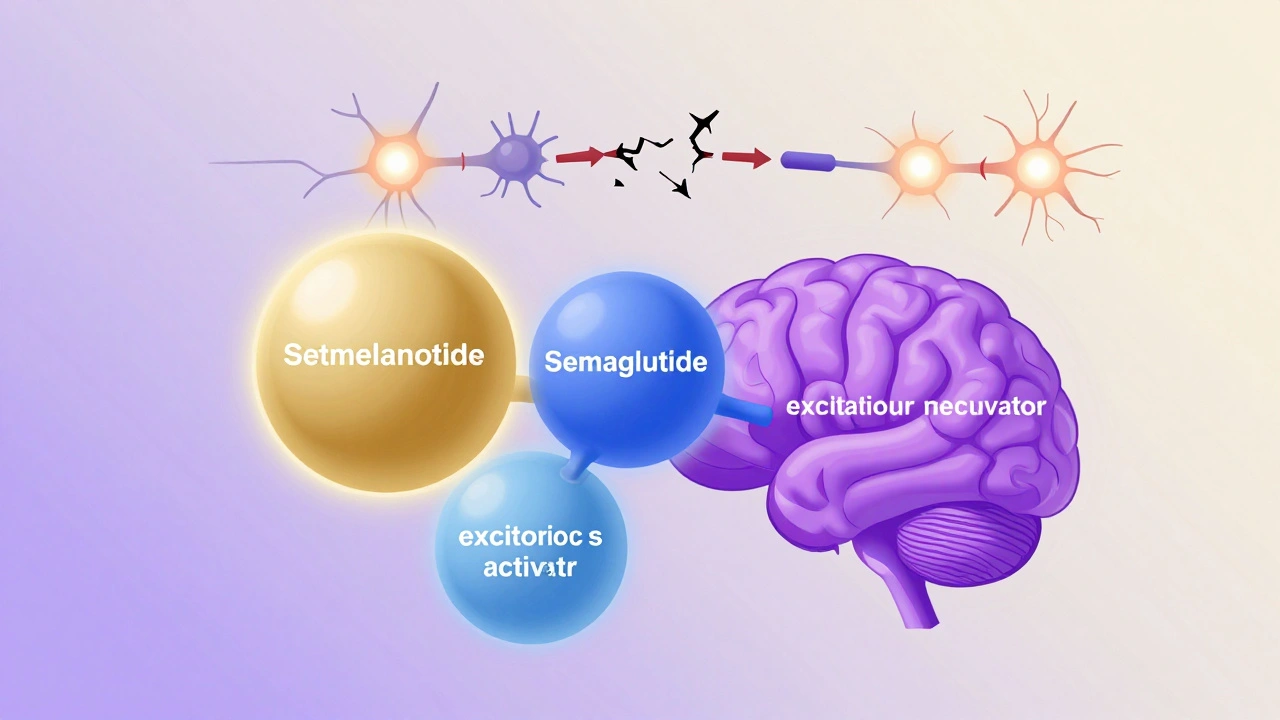

Most diets work short-term because they cut calories. But your body fights back. As you lose weight, leptin drops. Ghrelin rises. Your metabolism slows. Your brain interprets this as famine. That’s why weight loss plateaus-and why most people regain the weight. The real breakthroughs are coming from drugs that bypass broken signals. Setmelanotide, for example, directly activates the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R), the final step in the POMC pathway. In people with rare genetic mutations in POMC or LEPR genes, it cuts weight by 15-25%. It doesn’t work for everyone, but it proves that fixing one broken link can reset the whole system. Semaglutide, originally a diabetes drug, mimics GLP-1-a gut hormone that slows stomach emptying and tells the brain you’re full. In trials, it led to 15% average weight loss. That’s not magic. It’s overriding the broken appetite signals with a stronger, external one. A 2022 discovery added another layer: scientists found a group of excitatory neurons right next to the hunger and fullness neurons in the arcuate nucleus. When these were activated in mice, eating stopped within two minutes. This could lead to new therapies that don’t just suppress hunger-but instantly shut it off.

Leptin resistance is wild when you think about it-your fat cells are screaming 'I've got energy!' but the brain's like 'Nah, we're starving.' It's not willpower, it's a broken radio signal. 🤯

And the fact that ghrelin doesn't drop after eating? That's why I'm still hungry 2 hours after a 700-calorie meal. Biology is rigged.

So we're not lazy we're just biologically hacked? That makes so much sense. I used to think it was just about calories in vs out but this is like your body's operating system has a virus and no one told you.

It's not about eating less, it's about fixing the feedback loop. If your phone's battery meter says 20% but it's actually at 80%, you're gonna keep plugging it in forever. Same thing.

Oh wow, so the real villain isn't pizza-it’s the JNK enzyme? And insulin is just chilling in your brain like 'yo, I'm here to help' but your neurons are like 'Nah, we don't trust you anymore.'

Meanwhile, I'm over here chugging protein shakes thinking I'm doing the right thing while my hypothalamus is literally screaming into a void. This is the plot of a sci-fi movie where the body betrays the mind. I'm not fat-I'm a victim of molecular treason.

Diets don't work

It's insane how much of this is about the brain not getting the right signals and how every hormone is playing telephone with your appetite and by the time the message gets there it's been distorted by inflammation and insulin resistance and leptin resistance and now your body thinks you're in a famine even though you're surrounded by snacks and the worst part is that your metabolism slows down because it's trying to survive and it's not your fault at all and people who say you just need to try harder are either ignorant or cruel or both and I wish more doctors understood this because I've been told to eat less for ten years and I've lost weight and gained it back five times and I'm exhausted and I just want my body to stop fighting me

So let me get this straight-your body is too dumb to know when it's full, so we should just hand out magic pills and call it a day? No discipline? No accountability? You're telling me someone can eat a whole pizza and blame their neurons? Pathetic. You think your body is a victim? Your body is a machine. You're just too lazy to program it right. Wake up.

Oh so now it's not my fault I ate the whole tub of ice cream because my serotonin receptors are on vacation? Cool. So next time I binge-watch Netflix and eat chips till 3am, I'll just say 'my mTOR signaling is sluggish.' Genius. The real disease here is the delusion that biology excuses behavior. You're not a lab rat. You're a human with choices. Or at least you used to be.

While the biochemical mechanisms described are indeed compelling, it is imperative to recognize that the sociopolitical implications of pathologizing obesity as a purely neuroendocrine disorder may inadvertently undermine the necessity of behavioral and environmental interventions. The conflation of biological determinism with moral neutrality risks the normalization of deleterious lifestyle patterns under the guise of scientific legitimacy. One must not conflate mechanistic understanding with moral absolution. The body may be broken-but the will remains, and ought to be cultivated, not abdicated.