What is Retinal Vein Occlusion?

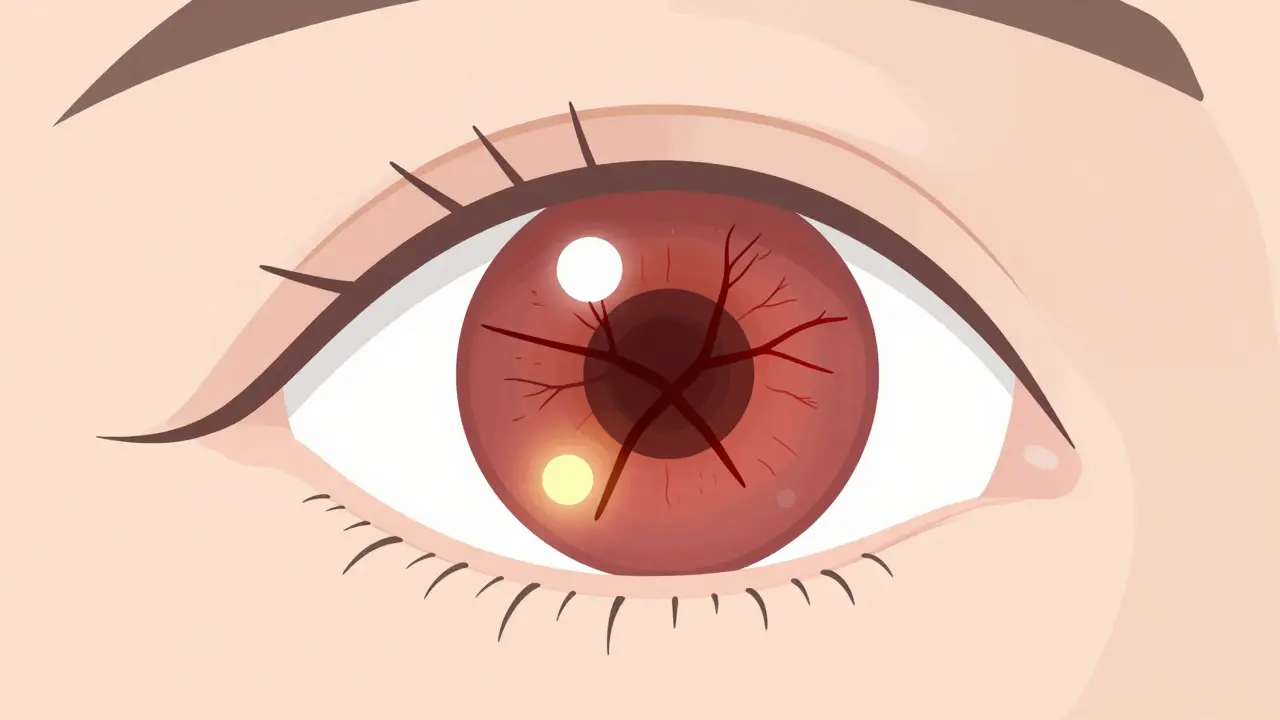

Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO) happens when a vein in the retina gets blocked, stopping blood from flowing out. This causes fluid to leak, swelling in the macula - the part of your eye responsible for sharp central vision. The result? Sudden, painless blurring or loss of vision in one eye. It doesn’t hurt, which is why many people ignore it until it’s too late.

There are two main types: Central Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO), which blocks the main vein, and Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion (BRVO), which affects smaller branches. BRVO is more common and often happens where a hard artery presses down on a vein - like a kinked garden hose. CRVO is more serious and tends to cause worse vision loss.

It’s not rare. Around 16.4 million people worldwide have had RVO, and it’s one of the top three causes of vision loss in adults over 50. The good news? Treatment has improved dramatically in the last decade. The bad news? If you don’t get help fast, damage can become permanent.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Age is the biggest red flag. Over 90% of CRVO cases happen in people over 55, and more than half of all RVO cases occur in those over 65. But it’s not just an older person’s disease. About 5-10% of cases strike people under 45 - and when it does, there’s usually something else going on.

High blood pressure is the number one risk factor. Up to 73% of CRVO patients over 50 have it. Even if your blood pressure is just slightly elevated, it puts pressure on the delicate veins in your eye. Uncontrolled hypertension is especially dangerous for BRVO.

Diabetes is another major player. About 10% of RVO patients over 50 have diabetes, and if you’re diabetic, your chances of poor vision recovery are higher. High cholesterol - specifically total cholesterol above 6.5 mmol/L - shows up in 35% of RVO cases, no matter your age.

Glaucoma raises your risk too. If you have high eye pressure, especially near the optic nerve, it can squeeze the retinal vein. Smoking? It’s in about 25-30% of cases. Being overweight and inactive adds to the problem by making your blood thicker and slower to move.

For younger women under 45, birth control pills are a surprising link - especially with CRVO. If you’re on the pill and suddenly lose vision, get checked right away. Blood disorders like polycythemia vera, leukemia, or clotting problems like factor V Leiden also increase risk in younger patients.

How Are Injections Used to Treat RVO?

Injections are now the standard treatment - not for the blockage itself, but for the swelling it causes. When fluid leaks into the macula, it creates macular edema. That’s what blurs your vision. The injections stop the fluid.

There are two main types: anti-VEGF and corticosteroid injections.

Anti-VEGF drugs - like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) - block a protein that causes leaky blood vessels. They’re the first choice for most patients. In clinical trials, patients gained 15-18 letters on the eye chart after a few months of monthly shots. That’s like going from 20/200 to 20/60 - enough to read a phone screen again.

Corticosteroid injections, like Ozurdex (dexamethasone implant), are used when anti-VEGF doesn’t work well enough. They reduce swelling longer but come with risks: cataracts in 60-70% of patients who still have their natural lens, and eye pressure spikes in about 30%.

Most doctors start with monthly anti-VEGF shots until the swelling goes down. Then they switch to as-needed dosing. Real-world data shows patients need 8-12 injections a year to keep vision stable.

What’s the Real-World Experience Like?

For many, the injections are life-changing. One man in his 60s went from barely seeing his grandchildren to reading their names on a birthday card after four Lucentis shots. Another patient, who’d tried eight Avastin injections with no progress, got a single Ozurdex implant and gained 10 lines of vision.

But it’s not all easy. The cost is brutal. In the U.S., Lucentis or Eylea can cost $2,000 per shot. Avastin, which is the same drug but repackaged, costs about $50. Many people in safety-net hospitals get Avastin because it’s affordable. But private clinics often use the pricier options.

Then there’s the emotional toll. People talk about the anxiety before each injection - the fear of pain, infection, or losing more vision. Some develop injection fatigue and skip appointments. One woman missed three visits in a row because she was too scared. Her vision kept improving, but she couldn’t bring herself to go back.

Side effects are usually minor: a red spot on the white of the eye, floaters, or temporary pressure. Serious infections like endophthalmitis happen in fewer than 1 in 1,000 injections. Still, the fear lingers.

How Is It Diagnosed and Monitored?

It starts with a simple eye exam. Your doctor checks your vision, looks at the back of your eye with a special light, and checks your eye pressure. But that’s just the beginning.

The real key is optical coherence tomography (OCT). This scan shows the layers of your retina in detail. If the macula is swollen, it shows up as thickening. Doctors track the central subfield thickness - if it’s over 300 micrometers, treatment starts. When it drops below 250, they may pause injections.

Fluorescein angiography is another tool. A dye is injected into your arm, and photos are taken as it flows through the eye’s blood vessels. This shows exactly where the blockage is and if new, leaky vessels are forming.

The whole process takes less than 15 minutes. The injection itself? Five to seven minutes. You get numbing drops, your eye is cleaned with iodine, a tiny speculum holds your eyelid open, and a needle goes in - no stitches needed. Most people feel pressure, not pain.

What’s New in RVO Treatment?

The future is about fewer shots and smarter choices.

A new approach called treat-and-extend is gaining ground. Instead of monthly shots, you start with monthly injections, then slowly stretch the time between them - from four weeks to six, then eight, then twelve - as long as your eye stays stable. A 2023 study showed this method gives the same results as monthly shots but cuts injection frequency by 30%.

Another breakthrough? Combination therapy. Some patients respond better to a mix of anti-VEGF and steroid. One doctor found that patients with very poor vision at diagnosis (worse than 20/200) did better starting with a steroid implant, while those with better baseline vision did best with anti-VEGF alone.

Looking ahead, gene therapy is on the horizon. RGX-314 is a one-time injection that makes your eye produce its own anti-VEGF protein. It’s in clinical trials and could mean no more monthly shots for years. There’s also OPT-302, a new drug that blocks a different part of the VEGF system, being tested with Eylea for stubborn cases.

And then there’s Susvimo - a tiny pump implanted in the eye that slowly releases ranibizumab. Approved for macular degeneration, it’s now being tested for RVO. If it works, patients might only need refills every three months instead of monthly shots.

What Should You Do If You’re Diagnosed?

First, don’t panic. Vision loss from RVO isn’t always permanent - especially if you act fast. Get treatment within weeks, not months.

Second, manage your health. Control your blood pressure. Get your cholesterol and blood sugar checked. Quit smoking. Lose weight if you need to. These aren’t just "good ideas" - they’re part of your treatment plan.

Third, talk to your doctor about your options. Ask: "Is Avastin an option?" "Can we try treat-and-extend?" "Should we consider a steroid implant?" Don’t assume the first drug offered is the only one.

Finally, stay consistent. Missing injections hurts your long-term vision. If you’re scared, tired, or broke - tell your doctor. There are patient assistance programs, biosimilars coming soon, and ways to reduce the burden. You’re not alone in this.

What’s the Outlook?

Five years ago, RVO meant a high chance of permanent vision loss. Today, 78% of patients on anti-VEGF therapy report significant vision improvement after a year. That’s a huge win.

The challenge now isn’t just treating the eye - it’s managing the burden. The cost, the frequency, the anxiety. But the field is moving fast. With smarter protocols, cheaper drugs, and new technologies, the goal isn’t just to save vision - it’s to make treatment sustainable.

If you or someone you know has RVO, the message is clear: get help, stick with it, and ask questions. Your vision is worth it.

i got rvo last year and honestly? the injections are a nightmare. my eye turns red every time and i swear i can feel the needle scraping my eyeball. but hey, at least i can see my cat again. #winning

Thank you for this comprehensive and compassionate overview. As a healthcare professional in Ontario, I’ve witnessed the profound impact of timely anti-VEGF therapy. The emotional toll on patients is often underestimated-compassion must accompany clinical precision. 🙏

So let me get this straight. We’re injecting expensive drugs into people’s eyes to fix a problem caused by their own bad lifestyle choices? High blood pressure? Diabetes? Smoking? Yeah, I’m not surprised we’re broke. Someone should’ve just told them to eat less sugar and quit smoking before they turned their retina into a swamp.

Bro. I had a cousin who got one of those shots and now he sees like a hawk. Like, he read a whole book in one day. But then he said the doctor poked his eye with a needle and he cried like a baby. So like... is it worth it? I don't know man. I'm just saying.

The emotional resilience required of patients undergoing repeated intraocular injections is profoundly underdiscussed. The dignity maintained through vulnerability deserves recognition, not just clinical metrics. This post rightly humanizes the journey.

Let’s be honest: the fact that Avastin-a drug meant for cancer-is being repurposed as a $50 eye injection while Lucentis costs $2,000 is not just a healthcare issue. It’s a moral failure disguised as pharmaceutical innovation. The FDA should be ashamed. And don’t get me started on the 'treat-and-extend' scam. It’s just cost-cutting with a fancy name.

they don't want you to know this but rvo is caused by the globalist shadow network to make people dependent on big pharma. they inject you with chemicals so you keep coming back. they even made the eye doctor's needle too small so you don't feel it... that's how they control you. i saw it on a forum in nigeria. they don't want you to know about the real cure: vitamin d and prayer.

To anyone reading this and feeling overwhelmed: you’re not alone. Every injection, every appointment, every fear you feel is valid. But you’re also stronger than you think. Reach out. Talk to your care team. Ask about financial aid. There are people who want to help you keep your vision-and your peace. You’ve got this.