When you hear the word "biosimilar," you might think it’s just another name for a generic drug. But that’s not true. Biosimilars are not generics. They’re not even close. Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs, like aspirin or metformin. Biosimilars are copies of complex biological drugs-medicines made from living cells, like antibodies, hormones, or proteins. These drugs treat serious conditions: cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and more. Because they’re made from living systems, no two batches are exactly alike. That’s why the FDA doesn’t just approve them like it does generics. It runs a deep, multi-layered scientific review to prove they’re as safe and effective as the original.

How the FDA Approves Biosimilars

The FDA doesn’t "rate" biosimilars like it rates generic drugs with an AB rating. Instead, it evaluates them for biosimilarity. That means the biosimilar must be "highly similar" to the reference product-with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency. The process starts long before any human trials. It begins in a lab with advanced instruments that analyze the molecule down to its atomic structure.

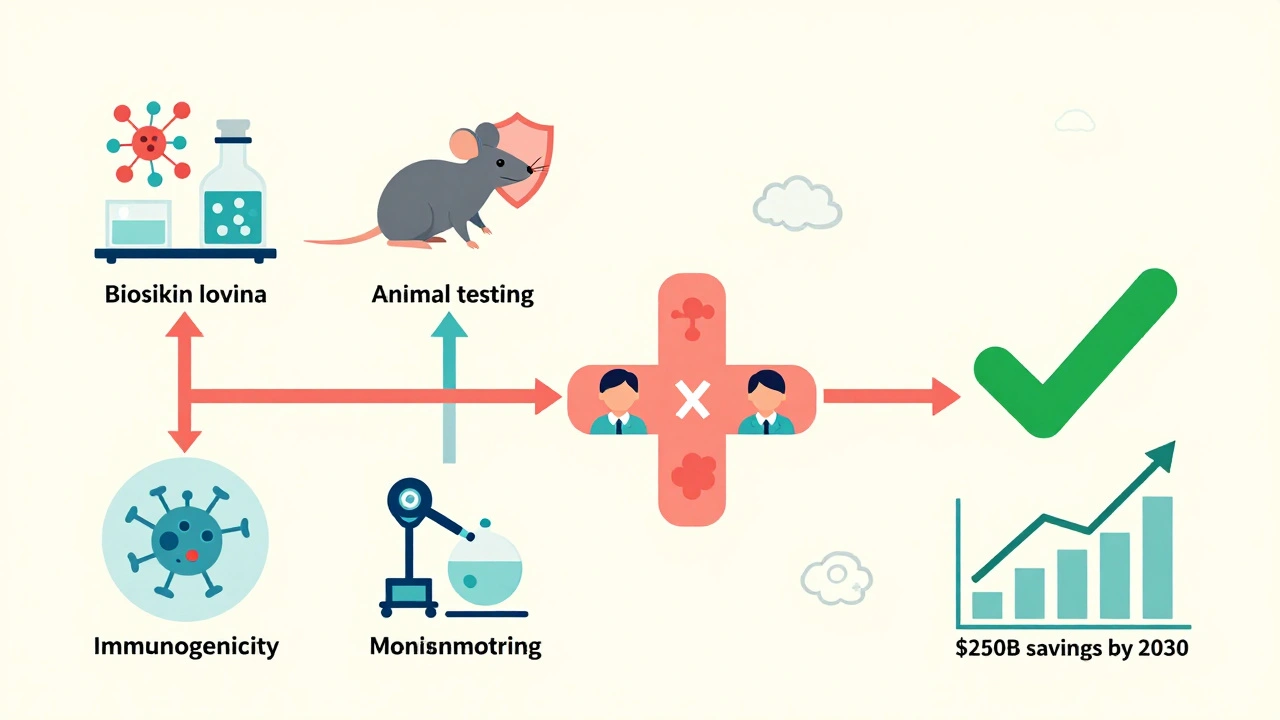

Manufacturers must show that their biosimilar matches the reference product across 200 to 300 critical quality attributes. These include things like molecular weight, amino acid sequence, glycosylation patterns, and protein folding. The FDA requires 95% to 99% similarity for most of these attributes. That’s not a suggestion-it’s a hard requirement. If even one key feature falls outside that range, the application gets rejected.

Once analytical data proves high similarity, the next step is usually animal studies to check for toxicity. Then, human studies follow: pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) trials in healthy volunteers or patients. These are typically small-50 to 100 people-and use a crossover design where participants get both the biosimilar and the reference product at different times. The goal isn’t to prove the biosimilar works better, but to prove it works the same.

Immunogenicity is another major hurdle. Biologics can trigger immune responses. Even a tiny difference in structure might cause the body to attack the drug, reducing its effectiveness or causing side effects. So manufacturers must monitor immune reactions over 24 to 52 weeks. The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative has tracked over 10 million patient-years of biosimilar use since 2015. So far, there’s no evidence that approved biosimilars cause more immune reactions than the originals.

The Purple Book: The Official FDA Listing

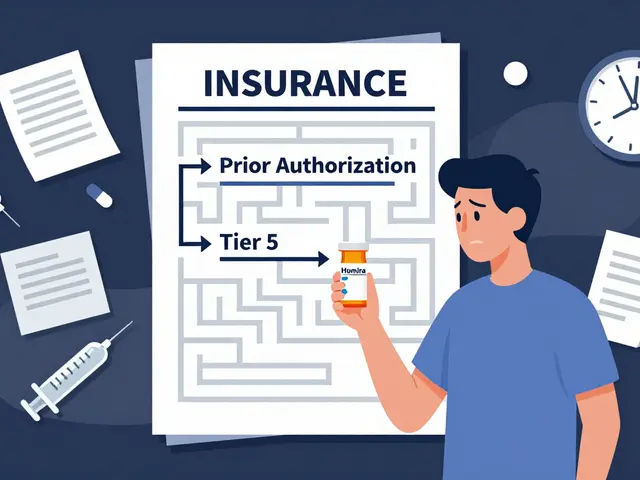

If you want to know which biosimilars are approved in the U.S., you go to the Purple Book. It’s the FDA’s official database of all licensed biologics-both reference products and their biosimilars. Unlike the Orange Book for generics, the Purple Book includes patent information, exclusivity periods, and licensure dates. It was updated in 2021 to require reference product sponsors to share patent details with biosimilar developers within 30 days of disclosure.

As of October 2025, the Purple Book lists 387 reference biologics and 43 approved biosimilars. Only 17 of those are designated as "interchangeable." That’s a higher standard. An interchangeable biosimilar must show that switching between it and the reference product won’t increase safety risks or reduce effectiveness. So far, only products like adalimumab and insulin biosimilars have reached this level. Most are still labeled as "biosimilar"-meaning they can be prescribed, but a pharmacist can’t substitute them without the doctor’s approval.

Biosimilars vs Generics: The Key Difference

Here’s the simplest way to understand the difference:

- Generics: Chemically identical to the brand-name drug. Made from simple molecules. The FDA only needs to prove bioequivalence-same absorption, same blood levels.

- Biosimilars: Nearly identical, but not exact. Made from living cells. The FDA must prove biosimilarity through thousands of tests, animal studies, and human trials.

Think of it like this: a generic is a photocopy of a handwritten note. A biosimilar is a hand-drawn replica of a painting. You can’t just match the colors-you have to match the brushstrokes, the texture, the layering. That’s why biosimilars cost more to develop than generics. A typical generic might cost $1 million to bring to market. A biosimilar? $120 million to $180 million.

Why the Process Takes So Long

It’s not just science-it’s also legal. Many biosimilars get delayed by patent lawsuits. Even after the FDA approves a biosimilar, the original drug maker can sue to block it. Between 2015 and 2025, the FDA approved 43 biosimilars. But only 29 actually reached the market. The average delay between approval and launch? 11.3 months. That’s because drug companies often hold dozens of patents on a single biologic, creating what’s called a "patent thicket."

Manufacturing is another bottleneck. Biosimilars require specialized facilities, trained scientists, and advanced tools like mass spectrometers and capillary electrophoresis machines. A single analytical study can take 10 to 12 months. One company told the FDA that developing a biosimilar requires 200 to 300 person-years of scientific work. That’s the equivalent of five full teams working for five years.

What’s Changing in 2025

The FDA has made big changes to speed things up. In September 2024, it updated its guidance to allow manufacturers to skip comparative clinical trials if analytical data is strong enough. That’s a major shift. Before, every biosimilar needed a full clinical trial. Now, for well-characterized proteins like monoclonal antibodies, companies can rely on advanced analytics alone. This could cut development time by 12 to 18 months and save $50 million to $100 million per product.

In June 2025, the FDA introduced a new rule: biosimilars can now get approval for all indications of the reference product based only on analytical data-no extra clinical studies needed. This is called "extrapolation." For example, if a biosimilar is approved for rheumatoid arthritis, and the original drug is also approved for psoriasis and Crohn’s, the biosimilar can be approved for all three without testing it in patients with psoriasis or Crohn’s.

The Purple Book is now a live, searchable database with daily updates. And the FDA is testing AI tools to analyze analytical data faster. These changes are already working. In 2024, the U.S. biosimilar market hit $12.7 billion-up from $1.2 billion in 2018. Analysts predict it will hit $250 billion in savings by 2030.

Who Benefits?

Patient groups like the Cancer Support Community have praised the FDA’s strict standards. They say the rigorous review has kept patients safe. Real-world data from the FDA’s Sentinel system shows adverse event rates for biosimilars are statistically the same as for the original drugs-about 0.8 per 10,000 patients, compared to 0.7 for the reference products.

But cost savings aren’t automatic. Even though biosimilars are cheaper to make, many insurers and pharmacy benefit managers still favor the original brand. In autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, adalimumab biosimilars launched in 2023 only captured 28% of the market by mid-2025. In cancer, though, biosimilars for rituximab and trastuzumab have taken over 65% to 75% of the market within 18 months. Why? Oncologists are more comfortable switching. They see the data. They trust the science.

What’s Next?

The next frontier is complex biosimilars-things like antibody-drug conjugates and fusion proteins. So far, only three applications for these have been submitted. None have been approved. The FDA says it’s working on new guidance for these products, expected by Q3 2026.

Another challenge: gene therapies. These are the next generation of biologics. But there’s no clear way to measure biosimilarity for them yet. The FDA admits this is the biggest regulatory gap. Without standardized methods, biosimilars for gene therapies can’t be approved.

For now, the U.S. system is slower than Europe’s. The EMA has approved 118 biosimilars. The FDA has approved 43. But the FDA’s standards are stricter. And that matters. When a patient gets a biosimilar, they need to know it’s not just similar-it’s safe. And the FDA’s process ensures that.

Are biosimilars the same as generics?

No. Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs and are approved based on bioequivalence. Biosimilars are copies of complex biological drugs made from living cells. They are highly similar but not identical, and require extensive analytical, animal, and human testing to prove safety and effectiveness.

What is the FDA Purple Book?

The Purple Book is the FDA’s official list of all licensed biologics, including reference products and their approved biosimilars. It includes licensure dates, exclusivity periods, and patent information. It was updated in 2021 to improve transparency and help biosimilar developers navigate intellectual property issues.

What does "interchangeable" mean for a biosimilar?

An interchangeable biosimilar meets a higher FDA standard: it can be substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist without the prescriber’s permission. To qualify, it must show that switching between the biosimilar and the original won’t increase safety risks or reduce effectiveness. Only 17 of the 43 approved U.S. biosimilars have this designation as of 2025.

Why are biosimilars so expensive to develop?

Biosimilars require thousands of analytical tests to prove similarity to the original biologic. The process involves advanced techniques like mass spectrometry and chromatography, and can take 10-12 months just for the analytical phase. Development costs average $120-180 million, compared to $1 million for a typical generic drug.

Can a biosimilar be used for all the same conditions as the original drug?

Yes, under a process called "extrapolation." If a biosimilar is proven similar to the reference product in one condition, and the mechanism of action is the same across other uses, the FDA can approve it for all indications without requiring separate clinical trials for each. This was formalized in FDA guidance in June 2025.

Why haven’t more biosimilars reached the market in the U.S.?

Patent litigation is the biggest barrier. Even after FDA approval, brand-name manufacturers often sue to delay market entry. Between 2015 and 2025, the FDA approved 43 biosimilars, but only 29 have launched. The average delay between approval and launch is 11.3 months. Payer restrictions and prescriber hesitation also slow adoption, especially in autoimmune diseases.

Biosimilars are a game changer, honestly. I’ve seen patients switch from Humira to its biosimilar and save thousands a year without a single side effect. The science is solid, and the FDA’s process isn’t just bureaucratic-it’s necessary.

Let’s not forget the PK/PD crossover trials-they’re the unsung heroes of biosimilar approval. Small cohorts, but the data’s clean as a whistle. And immunogenicity monitoring over 52 weeks? That’s not padding, that’s due diligence.

Wait-so you’re telling me we’re approving drugs that aren’t even identical? And calling them ‘safe’? This is why people don’t trust the FDA. They cut corners with biosimilars, then act like it’s a victory. It’s not. It’s a compromise. And patients are the ones paying the price.

One cannot help but observe that the regulatory architecture surrounding biosimilars reflects a profound epistemological tension: the desire for accessibility versus the imperative of ontological fidelity. The molecule, as a living artifact, resists reductionism; to equate its complexity with that of a small-molecule generic is not merely inaccurate-it is philosophically incoherent. The FDA’s multi-layered analytical rigor, though costly, is not merely procedural-it is ontologically necessary.

Furthermore, the Purple Book’s inclusion of patent disclosures constitutes a tacit acknowledgment that intellectual property, not therapeutic efficacy, remains the true gatekeeper of pharmaceutical access. One must ask: is this a triumph of science-or a triumph of legal stratagem?

And yet, the patient outcomes, as documented by the Sentinel Initiative, remain statistically indistinguishable. Does this validate the process? Or merely normalize the erosion of therapeutic certainty? The data does not answer the question-it merely reframes it.

One might argue that biosimilars represent a form of pharmaceutical utilitarianism: the greatest good for the greatest number, even if the means are imperfect. But utilitarianism without epistemic humility is tyranny dressed in white coats.

The real tragedy is not the delay in approval-it is the public’s inability to comprehend why such complexity is required. We have become a society that demands simplicity in the face of profound biological intricacy. And that, perhaps, is the most dangerous drug of all.

Let’s be real-biosimilars are just Big Pharma’s way of rebranding their monopoly. They spend $150M to make a copy, then charge 70% of the original price because ‘it’s complicated.’ Meanwhile, the generic aspirin makers laugh all the way to the bank. The FDA’s ‘strict standards’ are just a velvet rope for the rich.

And don’t get me started on ‘interchangeable.’ That’s not a scientific term-it’s a marketing buzzword invented by lobbyists who think ‘substitution’ sounds scarier than ‘switching.’

Also, who approved the Purple Book’s name? Was this a bet between interns? ‘Orange Book’ for generics, ‘Purple Book’ for biosimilars? Next they’ll release the ‘Rainbow Book’ for psychedelics.

Big fan of the extrapolation rule change. I work in oncology and we’ve seen trastuzumab biosimilars take over 70% of the market in under a year. Patients don’t care if it’s a photocopy or a painting-they care if it works and doesn’t bankrupt them. The science checks out. Let’s stop overthinking it.

i just had my mom switch to a biosimilar for her rheumatoid arthritis and she’s been fine for 8 months. no issues. why is everyone making this so hard?

It’s encouraging to see the FDA move toward evidence-based efficiency. The shift allowing analytical data to replace full clinical trials for monoclonal antibodies is a milestone. This isn’t cutting corners-it’s leveraging decades of accumulated knowledge to reduce redundancy. The savings will ripple through the entire healthcare system.

And the Purple Book’s live updates? Finally. Transparency isn’t optional-it’s the foundation of trust in biologics.

Just returned from a conference in London-EMA has approved over 100 biosimilars. We’re playing catch-up here, not because we’re cautious, but because we’re litigious. Patent thickets are the real barrier, not science.

Also, the 17 interchangeable biosimilars? That’s the real story. Pharmacists need clarity. Let them substitute. Patients deserve that convenience.

Thank you for sharing this. As a nurse who’s administered both reference biologics and biosimilars for over a decade, I can say with certainty: the outcomes are the same. The fear around biosimilars is mostly misinformation. We need more education-not more lawsuits.

And to the folks worried about immunogenicity: the data’s been tracked for millions of patient-years. The numbers don’t lie. Trust the science, not the noise.

Life is a biosimilar. Not exact. But close enough.

I’ve seen this play out in India too. Biosimilars brought TNF inhibitors to patients who’d never afford them before. The science isn’t perfect-but neither is access. Sometimes ‘close enough’ is the most ethical choice we have.

And yes, the cost difference is insane. One dose of original Humira: $2,500. Biosimilar: $500. That’s not a loophole-that’s justice.

Okay, let’s be honest here-this whole biosimilar thing is just a corporate shell game. The original drug companies spend billions on R&D, then sit on patents for 12 years, then when the clock runs out, they turn around and sue the biosimilar makers for ‘infringing on secondary patents’-like, what? You didn’t invent the molecule, you just found a way to make it cheaper, and now you’re crying about it?

And don’t get me started on the ‘interchangeable’ label. That’s just a fancy way of saying ‘we’ll let pharmacists switch it, but only if you sign a waiver and promise not to blame us if your immune system throws a tantrum.’

Meanwhile, patients are still paying $10,000 a year for insulin because the ‘biosimilar’ version is priced at $8,000. That’s not savings-that’s price gouging with a PhD.

And the Purple Book? That’s just a legal document disguised as a scientific resource. It’s not about safety-it’s about who owns the rights to your life-saving drug.

They say biosimilars will save $250 billion by 2030. But where’s that money going? Not into your pocket. Not into mine. It’s going into the pockets of the same CEOs who made the original drug unaffordable in the first place.

So yes, the science is impressive. But the system? It’s still rigged.

Let’s cut the crap. The FDA’s ‘rigorous’ process is just a delay tactic. Look at the numbers: 43 approved, 29 launched. The rest are stuck in courtrooms because Big Pharma owns the judges. This isn’t science-it’s a tax on innovation.

And the ‘120 million dollar cost’? That’s not R&D-it’s legal fees. The real biosimilar developers are out there, but they’re getting crushed by patent trolls with more money than sense.

Also, why is ‘interchangeable’ so rare? Because the brand-name companies pay pharmacies to not substitute. It’s not about safety-it’s about kickbacks.