When your stomach feels like it’s on fire-burning, bloated, or achy after eating-it’s easy to blame spicy food or stress. But if the discomfort keeps coming back, you might be dealing with gastritis: inflammation of the stomach lining. It’s not just a bad case of indigestion. For many people, especially those over 40, this isn’t a one-time glitch. It’s a sign that something deeper is going on. And in most cases, the culprit is a tiny, stubborn bacteria called Helicobacter pylori.

What Exactly Is Gastritis?

Your stomach has a protective mucus layer that keeps its own digestive acids from eating through its walls. When that layer gets damaged, the acid starts to irritate the tissue underneath. That’s gastritis. It’s not one disease-it’s a spectrum. Some people get sudden, sharp pain after drinking too much alcohol or popping a handful of ibuprofen. That’s acute gastritis. Others have a slow, silent burn that creeps up over years. That’s chronic gastritis.

The real difference? Erosive vs. nonerosive. Erosive means there are actual breaks in the lining-you might see blood in vomit or black, tarry stools. Nonerosive looks normal on the surface but has cellular damage underneath. That’s the kind often tied to H. pylori. About 70% to 90% of people with stomach ulcers have this bacteria living in their gut. And here’s the thing: most of them don’t even know it.

H. pylori: The Silent Saboteur

Before 1982, doctors thought stress and diet caused most ulcers. Then two Australian researchers, Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, proved otherwise. Marshall even drank a culture of H. pylori to prove it caused gastritis-then got sick. He won a Nobel Prize for it. Today, we know H. pylori infects nearly half the world’s population. In places like South Africa, India, or parts of Southeast Asia, up to 80% of adults carry it. In the U.S. and Europe, it’s lower-around 10% to 15%-but still common.

This bacteria doesn’t just sit there. It burrows into the stomach lining, weakens the mucus barrier, and tricks the immune system into causing long-term inflammation. Over time, that inflammation can lead to thinning of the stomach wall (atrophic gastritis), reduced acid production, and even changes that increase cancer risk. The good news? Treating it cuts your risk of stomach cancer in half.

Symptoms: Not Always Obvious

You might think gastritis means constant pain. But here’s the twist: up to half of people with chronic gastritis feel nothing at all. Others have vague symptoms that get dismissed as "just stress."

- Upper belly pain or burning (70-80% of cases)

- Nausea (60%)

- Bloating or feeling full fast (50%)

- Vomiting (40%)

- Loss of appetite

Red flags? Don’t ignore these:

- Black, tarry stools (melena)-a sign of internal bleeding

- Vomiting blood or material that looks like coffee grounds

- Fatigue, dizziness, or shortness of breath-signs of anemia from slow blood loss

If you’ve had any of these for more than a few days, see a doctor. Waiting won’t make it go away. It might make it worse.

Diagnosis: How Do You Know for Sure?

Doctors can’t diagnose gastritis by symptoms alone. You need tests.

The gold standard is an endoscopy. A thin camera goes down your throat, lets the doctor see the lining, and take tiny tissue samples (biopsies). These samples can confirm H. pylori, check for inflammation, and rule out cancer. It sounds scary, but it’s quick and done under light sedation.

There are also non-invasive options:

- Urea breath test: You drink a special liquid, then breathe into a bag. If H. pylori is there, it breaks down the urea and releases carbon dioxide you exhale. It’s 95% accurate.

- Stool antigen test: Checks for H. pylori proteins in your poop. Simple, cheap, reliable.

- Blood test: Looks for antibodies. But it can’t tell if the infection is current or past. So it’s not used for diagnosis anymore.

Most doctors start with breath or stool tests. If they’re positive, they’ll confirm with endoscopy if symptoms are severe or if you’re over 50.

Treatment: Eradicating H. pylori

If you have H. pylori, you’re not just treating symptoms-you’re fighting an infection. And you need a combo approach.

Standard treatment is triple therapy: a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like omeprazole or esomeprazole, plus two antibiotics-usually amoxicillin and clarithromycin-for 10 to 14 days. It works in 80-90% of cases… if you take it exactly right.

Here’s the catch: antibiotic resistance is rising. In the U.S., clarithromycin resistance jumped from 10% in 2000 to over 35% today. That means in some areas, the classic triple therapy fails more often than it works.

That’s why newer guidelines recommend:

- Bismuth quadruple therapy: PPI + bismuth + metronidazole + tetracycline. Used in places with high clarithromycin resistance. Success rate: 85-92%.

- Concomitant therapy: All four drugs given together for 10 days. Easier to follow than sequential regimens.

- Vonoprazan: A newer acid blocker approved in 2022. It works better than PPIs and is now used in first-line therapy in Japan and the U.S. Studies show 90%+ eradication rates-even after two failed treatments.

Side effects? Common. Diarrhea, metallic taste, nausea, or headaches during treatment. About 62% of patients report them. But they usually fade after you stop the meds. The key? Don’t quit early. Missing doses is the #1 reason treatment fails.

After treatment, you need a follow-up test-usually a breath or stool test-4 weeks later to confirm the bacteria is gone. Don’t skip this. If it’s still there, you’ll need a second round with different antibiotics.

Other Causes of Gastritis

H. pylori is the big one, but it’s not the only one.

- NSAIDs: Ibuprofen, naproxen, aspirin-even low-dose daily aspirin-can irritate the stomach lining. About 25-30% of cases are linked to these drugs.

- Alcohol: Heavy drinking (more than 30g/day) doubles your risk. Cutting back can reduce symptoms by 60% in just two weeks.

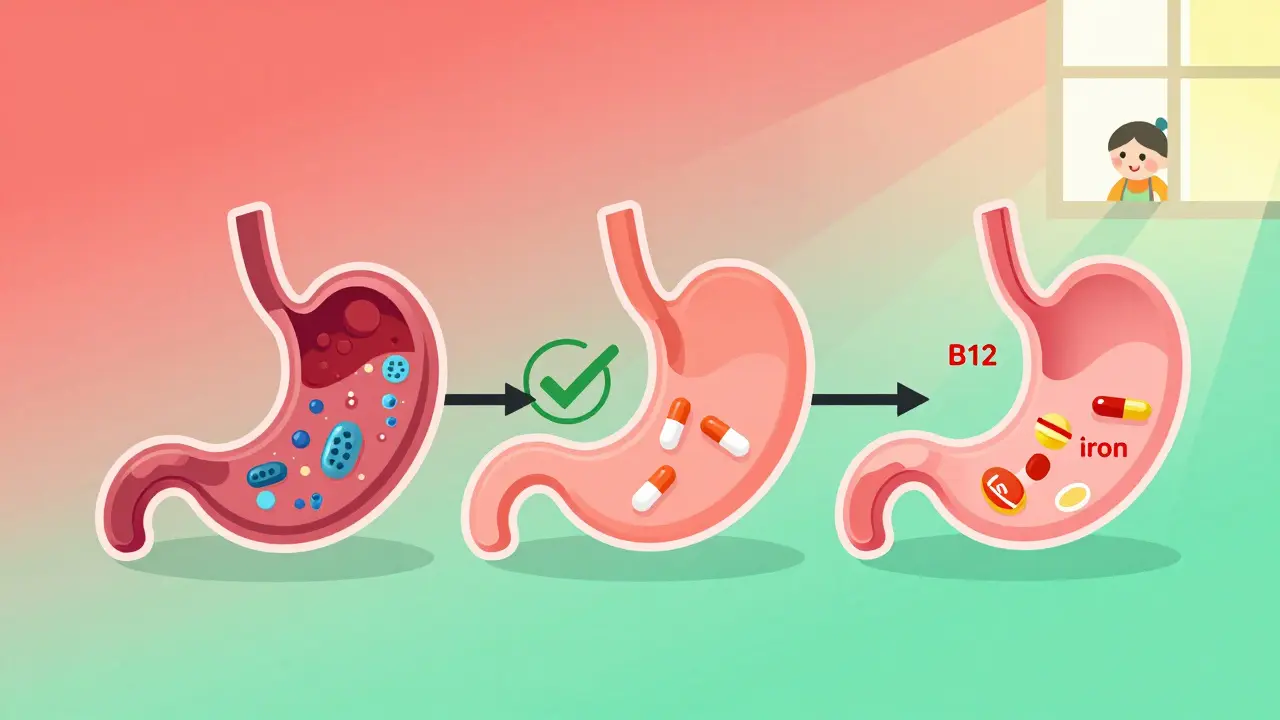

- Autoimmune gastritis: Your immune system attacks your own stomach cells. It’s rare (affects 0.1% of people) but common in those with thyroid disease or type 1 diabetes. It leads to vitamin B12 deficiency and needs lifelong B12 shots.

- Stress: Severe physical stress-like from burns, surgery, or ICU stays-can cause acute erosive gastritis. Not common in everyday life.

If you’re on long-term NSAIDs and have gastritis, your doctor might switch you to acetaminophen or prescribe a PPI alongside them.

Lifestyle Changes That Actually Help

Treatment isn’t just pills. Your daily habits matter.

- Quit smoking: Smoking slows healing. Quitting improves healing rates by 35%.

- Limit alcohol: Even moderate drinking can keep inflammation going.

- Avoid trigger foods: Spicy, acidic, or fried foods won’t cause gastritis, but they can make symptoms worse. Everyone’s different-track what bothers you.

- Eat smaller meals: Less pressure on your stomach means less burning.

- Don’t lie down after eating: Wait 2-3 hours before lying down or going to bed.

And here’s a myth: milk doesn’t soothe your stomach. It might feel good at first, but it later triggers more acid. Skip it.

The Long Game: What Happens After Treatment?

Getting rid of H. pylori doesn’t mean you’re done. If you had chronic gastritis, your stomach lining may still be damaged. Healing takes months. Some people develop atrophic gastritis, where the lining thins and stops making acid. That can lead to nutrient malabsorption-especially vitamin B12 and iron.

Long-term PPI use is another issue. Many people feel better and stop their meds… only to get rebound acid reflux. Up to 40% of long-term users experience this. The fix? Taper slowly, not cold turkey. Talk to your doctor about switching to H2 blockers (like famotidine) or using them only when needed.

And don’t assume you’re immune. Reinfection is rare in places like the U.S. but common in areas with poor sanitation. If you live in or travel to high-risk zones, be cautious with untreated water or street food.

When to Worry

Most gastritis isn’t dangerous. But some signs mean you need urgent care:

- Blood in vomit or black stools

- Unexplained weight loss

- Difficulty swallowing

- Severe, persistent pain that doesn’t improve

If you’re over 50 and have new stomach symptoms, get checked. Cancer risk increases with age, and early detection saves lives.

Final Thoughts

Gastritis isn’t something you just live with. It’s a treatable condition-with a clear path forward if you have H. pylori. The biggest mistake? Ignoring symptoms or quitting antibiotics early. The second biggest? Thinking it’s just "bad digestion." It’s not.

Take the test. Get the treatment. Follow up. Your stomach will thank you.

Can gastritis go away on its own?

Sometimes, yes-if it’s caused by a one-time trigger like alcohol or NSAIDs and you stop using them. But if H. pylori is the cause, it won’t go away without treatment. Left untreated, chronic gastritis can lead to ulcers, bleeding, or even stomach cancer.

Is H. pylori contagious?

Yes. It spreads through contaminated food, water, or close contact with an infected person’s saliva or vomit. It’s most common in childhood, especially in areas with poor sanitation. In developed countries, transmission is rarer but still possible through household sharing.

Do I need to repeat the H. pylori test after treatment?

Yes, if you were diagnosed with H. pylori. The treatment works 80-90% of the time, but not always. A follow-up breath or stool test 4 weeks after finishing antibiotics confirms whether the bacteria is gone. If it’s still there, you’ll need a different antibiotic combo.

Can I take antacids instead of antibiotics?

Antacids (like Tums or Maalox) or PPIs (like omeprazole) can relieve symptoms, but they don’t kill H. pylori. If you have the bacteria, you need antibiotics. Skipping them means the infection stays-and so does the risk of ulcers or cancer.

Are there natural remedies for H. pylori?

Some studies suggest honey, garlic, or probiotics may help reduce H. pylori levels, but none can replace antibiotics. They might support healing, but they won’t cure the infection. Don’t delay proper treatment for unproven remedies.

Why do some people with H. pylori never get sick?

About 80% of people infected with H. pylori never develop symptoms or complications. It depends on the bacterial strain, your genetics, diet, and immune system. Experts now recommend treating only those with symptoms, ulcers, or a family history of stomach cancer-not everyone who tests positive.