When a generic drug hits the market, you might assume it’s just a cheaper copy of the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it works the same way in your body? The answer lies in two numbers: Cmax and AUC. These aren’t just lab jargon-they’re the backbone of bioequivalence testing, the process that ensures generic drugs deliver the same therapeutic effect as their brand-name counterparts.

What Cmax Tells You About Drug Absorption

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration. It’s the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after you take it. Think of it like the peak of a mountain on a graph-how high does the drug climb before it starts to decline?

This number matters because some drugs only work when they hit a certain high point. Take painkillers like ibuprofen: if the Cmax is too low, you won’t feel relief fast enough. On the flip side, for drugs with a narrow safety margin-like warfarin or digoxin-a Cmax that’s too high can be dangerous. Too much in the blood too quickly can cause bleeding or heart rhythm problems.

Regulators don’t just look at the number. They also track Tmax, the time it takes to reach Cmax. If a generic drug hits its peak much faster or slower than the brand version, that’s a red flag. Even if the final concentration is the same, timing affects how you feel. A painkiller that takes 4 hours to kick in instead of 1 isn’t equivalent in practice, even if the total exposure is identical.

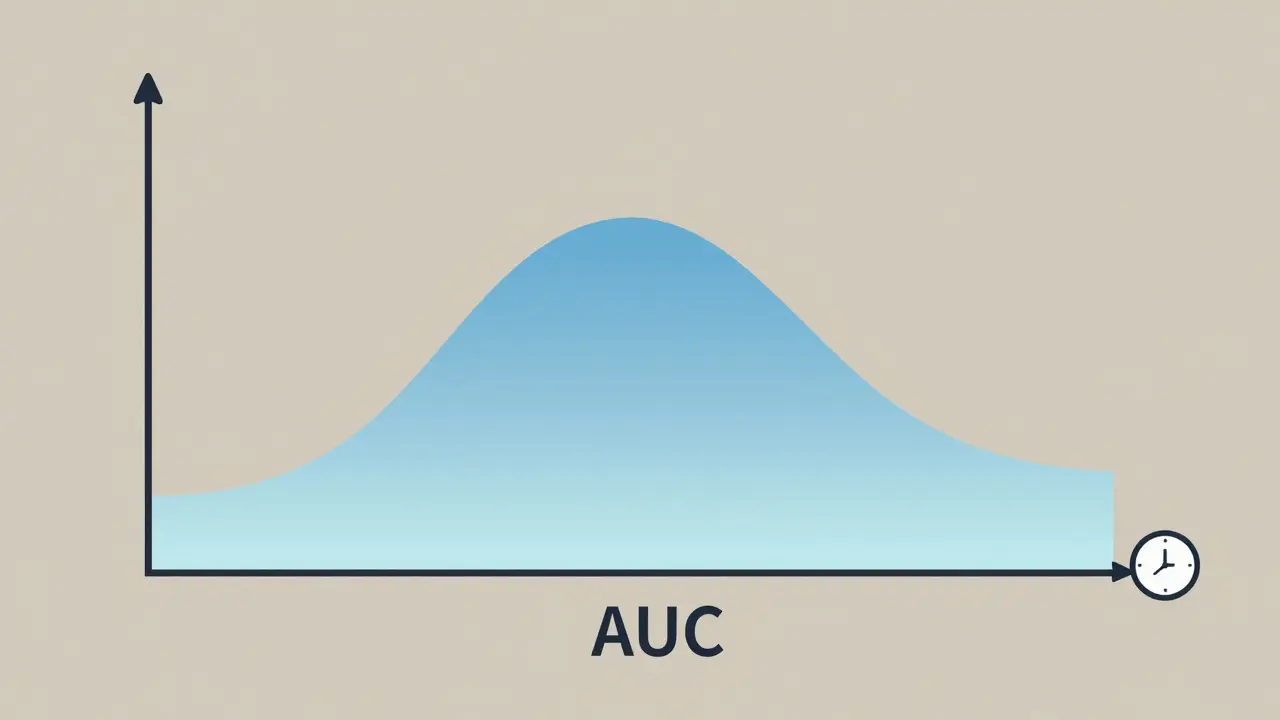

What AUC Reveals About Total Exposure

AUC, or area under the curve, measures the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. Imagine the drug concentration graph as a hill. AUC is the area underneath that hill-from the moment you swallow the pill until the drug is mostly gone from your system.

This is critical for drugs that need to stay in your system for a long time to work. Antibiotics like azithromycin, or blood pressure meds like lisinopril, rely on sustained exposure. If the AUC is too low, the drug doesn’t stick around long enough to be effective. Too high, and you risk side effects from buildup.

Unlike Cmax, which is a single snapshot, AUC is a cumulative measure. It accounts for how quickly the drug is absorbed, how long it lasts, and how fast your body clears it. Two drugs can have the same Cmax but wildly different AUCs-one might spike fast and vanish quickly, while the other rises slowly and lingers. That’s why both numbers are needed.

The 80%-125% Rule: How Bioequivalence Is Proven

Here’s the hard rule: for a generic drug to be approved, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of its AUC and Cmax values (compared to the brand drug) must fall between 80% and 125%. That means the generic’s exposure and peak levels can’t be more than 20% lower or 25% higher than the original.

This range wasn’t picked randomly. It came from decades of clinical data and statistical modeling. Back in the 1990s, regulators analyzed thousands of drug comparisons and found that differences smaller than this rarely led to real-world differences in safety or effectiveness. The logarithmic scale (ln(0.8) = -0.2231, ln(1.25) = 0.2231) was chosen because drug concentrations in blood don’t follow a normal bell curve-they follow a log-normal pattern. That’s why data is transformed before analysis.

And here’s the kicker: both AUC and Cmax must pass. If one meets the range and the other doesn’t, the drug fails bioequivalence. You can’t trade off one for the other. This dual requirement ensures that not only is the total exposure similar, but the speed of absorption is too.

Why Sampling Timing Matters More Than You Think

Getting accurate Cmax and AUC values isn’t just about running a lab test. It’s about when you draw the blood.

For fast-absorbing drugs, the first few hours after dosing are critical. If you miss sampling at 30 minutes, 1 hour, or 2 hours, you might completely miss the peak. That’s why studies require 12 to 18 blood draws over 3 to 5 half-lives of the drug. Missing even one key time point can throw off the entire curve.

Industry data shows that about 15% of bioequivalence studies fail because of poor sampling design-not because the drug is different, but because the data is incomplete. The EMA and FDA both stress that actual sampling times must be used, not assumed times. If a sample was taken at 1.8 hours, not 2.0, you use 1.8. Tiny differences matter.

Modern labs use LC-MS/MS (liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry) to measure drug levels as low as 0.1 nanograms per milliliter. That’s like finding a single drop of water in an Olympic-sized pool. Without this precision, you couldn’t trust the numbers.

When the Rules Get Tighter: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Not all drugs follow the 80%-125% rule. For drugs where small changes can cause big problems-like warfarin, lithium, phenytoin, or levothyroxine-the limits are stricter: 90% to 111%.

Why? Because these drugs have a razor-thin line between helping and harming. A 10% drop in exposure might mean a seizure. A 10% increase might mean internal bleeding. The FDA and EMA both recognize this and allow tighter bioequivalence criteria for these cases.

Even then, the same principles apply. You still need both AUC and Cmax to pass. But now, the margin for error is half as wide. This isn’t about being overly cautious-it’s about preventing real harm. Studies have shown that patients switching between generics and brand versions of these drugs can experience fluctuations in blood levels if bioequivalence isn’t tightly controlled.

What Happens When Bioequivalence Fails

Not every generic makes it through. When a study fails, the manufacturer has to go back and figure out why. Was the formulation wrong? Did the excipients interfere with absorption? Was the sampling schedule inadequate?

In some cases, companies redesign the tablet-change the coating, particle size, or manufacturing process-to match the brand’s performance. This isn’t just about copying. It’s about reverse-engineering the pharmacokinetics to match the original.

And yes, it’s expensive. Bioequivalence studies typically involve 24 to 36 healthy volunteers, run over 2 to 4 weeks, with multiple blood draws and lab analyses. The global market for these studies was worth $2.1 billion in 2022. That’s why generic drugs are cheaper than brand names-not because they’re low quality, but because they don’t need to repeat the multi-year clinical trials the original drug went through.

The Bigger Picture: Why This All Matters

Over 1,200 generic drugs were approved in the U.S. in 2022 alone. Nearly all of them relied on Cmax and AUC data. And here’s the proof it works: a 2019 analysis of 42 studies in JAMA Internal Medicine found no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness between generics and brand-name drugs that passed bioequivalence testing.

That’s the whole point. You shouldn’t have to pay $500 for a drug when a $20 generic does the same job. But you also shouldn’t risk your health because the generic didn’t absorb the same way.

Cmax and AUC are the gatekeepers. They’re not perfect, but they’re the best tools we have. They’ve been validated over 40 years, used in over 120 countries, and backed by regulatory agencies from the FDA to the WHO. They’re simple, measurable, and clinically meaningful.

As new drug forms emerge-like extended-release patches or complex nanoparticles-regulators are exploring new metrics. But for now, and for the foreseeable future, Cmax and AUC remain the gold standard. They’re not just numbers. They’re the quiet, scientific guarantee that your generic pill will work just like the brand name.

What does Cmax mean in bioequivalence studies?

Cmax stands for maximum plasma concentration-the highest level a drug reaches in your bloodstream after taking it. It tells regulators how quickly the drug is absorbed. For drugs where timing affects effectiveness or safety (like painkillers or heart medications), Cmax is critical. If a generic drug’s Cmax is too low or too high compared to the brand, it may not work the same way.

How is AUC different from Cmax?

AUC (area under the curve) measures total drug exposure over time, while Cmax is just the peak level. AUC tells you how much of the drug your body has been exposed to from start to finish. Two drugs can have the same Cmax but very different AUCs-one might spike fast and disappear quickly, while the other builds slowly and lasts longer. Both are needed to confirm full equivalence.

Why must both AUC and Cmax pass the 80%-125% rule?

Because bioequivalence means no significant difference in both the rate and extent of absorption. AUC covers the extent (how much you get), and Cmax covers the rate (how fast you get it). If only one passes, the drug might be absorbed too slowly or too quickly, even if the total exposure matches. Regulatory agencies require both to ensure the generic behaves identically in your body.

Are there exceptions to the 80%-125% bioequivalence range?

Yes. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, lithium, or levothyroxine-the acceptable range is tighter: 90% to 111%. These drugs have very little room for error; even small differences in exposure can cause serious side effects or reduced effectiveness. Regulators apply stricter limits to protect patients.

How are Cmax and AUC measured in bioequivalence studies?

Participants take the drug, and blood samples are drawn at 12 to 18 specific times over 3 to 5 drug half-lives. Labs use highly sensitive techniques like LC-MS/MS to measure drug concentrations down to nanogram levels. The data is then plotted, and AUC and Cmax are calculated using validated software. Logarithmic transformation is applied because drug levels follow a log-normal distribution, not a normal one.

Do bioequivalence studies always use healthy volunteers?

Yes, for most conventional oral drugs. Healthy volunteers are used because they eliminate confounding factors like disease, organ dysfunction, or other medications that could affect drug absorption. This gives regulators a clean comparison between the brand and generic. For some complex drugs-like inhaled or injectable products-studies may involve patients, but for standard pills and capsules, healthy volunteers are standard.

Why do some generic drugs still cause complaints if they’re bioequivalent?

Bioequivalence ensures the drug enters the bloodstream the same way, but it doesn’t control for things like taste, pill size, or inactive ingredients. Some patients report differences in how quickly they feel relief or side effects like stomach upset, which may be due to fillers or coatings-not the active drug. In rare cases, high variability between batches or poor manufacturing can cause issues, but these are exceptions, not the rule. Rigorous testing keeps most generics safe and effective.